Trying to add another dimension to my art, with watercoloring. Early dabblings in 2021. Here, in memoriam of Prince, in 2021.

pacyinz' poetry blog

Wednesday, April 21, 2021

Friday, March 19, 2021

Monday, March 22, 2021--BIPOC Writing Workshop's Spring Equinox and One Year Anniversary

Last March, Faith Adiele and Serena Lin started the Monday night BIPOC Writing Workshop, an online support vehicle for BIPOC writers at the beginning of the global pandemic lockdown. Faria Chaudhry and Miguel took over the facilitation under the Farigüel moniker. This weekly workshop has been a life support blessing for the 30 to 60 BIPOC writers from all around the country and even world, who find fellowship and creativity in this community. Good poetry and writing are generated and shared. Laughters and tears are shared. News, readings, and publications are shared. Happy to celebrate one year of fellowship and looking forward to hosting a breakout room to journey from Dark to Light with breath, a tiny bit of body language, some video poetic inspiration, and some writing to manifest better futures.

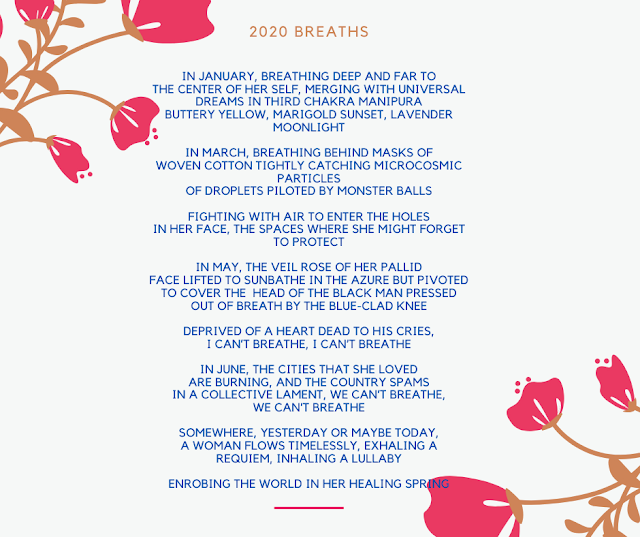

Monday, June 1, 2020

COVID-19 Virtual Artistic Life: Theater Mu's Variety Show, 5-22-20

One of the unexpected boons of COVID-19, which has made the situation much more bearable, has been the many free artistic offering from community arts organizations which can now routinely reach a national and international audience. Theater Mu, a Minnesota-based theater company, offers witty and social conscious programming. This specific cabaret style event showcased the broad range of the Asian American arts scene and talents. Not all performances are being reported here. From top to bottom of the photos above, which are in chronological order of performance:

- Mayda Miller, a well-known local musician, played her acoustic guitar and shared an original indie-rock song.

- Bao Phi, now one of the pioneers of the Asian Minnesotan poetry scene, shared a poem he published in UnMargin, an online magazine giving voice to different perspectives on social justice and progressive commentaries.

- Joelle Fernandez and Frankie Hebres, a husband and wife team of dancers, performed some old-style hip hop numbers.

- Gao Song V. Heu presented an opportunity to hear a traditional Hmong song, which will be part of a solo production putting on stage The Song Poet, a book by Kao Kalia Yang, a well-established Hmong Minnesotan writer, featuring the experiences of her father as a Hmong traditional singer.

- Sisters Francesca and Isabella Dawis contributed the classical singing and instrument playing of the evening, with a Salon-intimate repertoire.

Overall, it was a delightful evening of fun banter sprinkled with some serious remarks on Asian American arts. More of those variety shows would be welcome.

COVID-19 Publication: COVID-19 Bittersweet Recipe, in Another Chicago Magazine, 5-3-20

Saturday, August 3, 2019

2019 Asian American Literature Festival- August 2-4, Washington-DC, Day 1

Anyhoo, I don't want to spend tons of time writing about the first day of the festival, which is why I am writing this little photo blurb blog, before I can write something more profound. The Asian American Literature Festival: it is part personal journey, part professional journey, part community journey, part history, part building the future, and happening now. Definitely, check it out it when you can, now and here.

First Stop: Literary Lounge. There are tons of interesting tables, and I only spend 15 minutes there on the first day before rushing to my first workshop. Very first stop, because I am sometimes a bit superstitious, meaning I do believe in fate: Tarot Reading. A project about mental health, the tarot reading is in my own mind, the way that I want to check what the universe intends for me when it feels uncertain. Last time, I got Death, and it was accurate. I needed to die in order to be reborn. I did not want it. I did not enjoy it. Overall, it was ok. I did evolve to someone a bit better if not as naively happier. This year: the Adoptee. Ooookkkayyyy...alright more than on that later.

Literary Lounge: cool find. So, there is an organization called the 1882 Foundation, for the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act that prohibited the legal migration of Chinese people. Like its founders, a part of me loves the way that they took something ugly and painful and made it something they now own and gives them power. They and other partners from the Chinese American community in DC will open a Chinese American Museum in DC on 16th Street next year. Wow, that is something to look forward to.

Laomagination Session. In solidarity with my Laotian heritage and with my old friend from way back when we toddled around on our poetic baby feet, my first workshop had to be Laomagination. I had not seen my friend Bryan Thao Worra for 8 years. Within 5 minutes of spotting him gingerly trying to set up his props, I saw that Bryan will always be Bryan indeed: only Bryan would stumble upon power cords, drop the video camera every 5 seconds and dismount the table in 5 minutes. Yeah, that's Bryan alright, poetic genius and super geek. K, you do have to know Bryan for a bit longer to really get his genius part, but it is there, just not what most people think it is. With his lovely collaborator, Kaysone Syonesa, a poet/playwright/dancer.

I think I really wanted to catch up a bit more with my fellow Laotian American poets, plus I wanted to understand better what's going on with my friend Bryan, since we had not seen each other for so long. So, I just tagged along and talked a bit and observed. I guess we were on a mini tour of DC monuments as part of their Laomagination photo collecting. Of course, we had to stop by the Vietnam War Memorial, the Vietnam War being the Waterloo of us Laotian people. This photo expresses perfectly how I always feel about the Vietnam War in general and the Vietnam War memorial in particular: although our dead and we are there, they and we are only an outside reflection on the wall of the official war narrative.

My friend Bryan. Like a lot of my friends, it's all onion. :) You have to peel the layers to understand what's really there. Right now, he is really busy with his Laomagination project and his mentee/collaborator/sidekick, Kay.

On the way back from the national mall, we stopped by the Freer/Sackler Gallery where the evening Verbal Fire was taking place. Some of us sipped cocktails and wine, some of us ate thai tea ice cream. It was a good time to catch up with Lawrence Minh Bui Davis, the lead organizer for the Festival from the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Cultural Center. It's not visible here, but I immediately spotted, because my brain loves traditional jewelry: Lawrence was wearing a gorgeous black seed necklace, a gift from the Hawai'ian delegation.

Verbal Fire. Before we split for the rest of the night, we got a glimpse of the awesome Verbal Fire performance and contest about to take place in the Freer/Sackler Auditorium. Gowri Koneswaran was the MC: she is the professional MC, doing a beautiful job as MC. Bryan and Kay went to meet other fellows at Hanuman, the new Lao restaurant on H Street. I walked back to the hotel to catch the Kundiman Salon.

Kundiman Salon. Ah, Kundiman is the top of the cream of Asian American Literature. It's like the Harvard of Asian American Literature. It is so good, almost nobody I know actually got in. But hope springs eternal and we do apply every year. Anyhoo, I really enjoyed the Kundiman Fellow reading two years, and thought the quality of the poetry was excellent, on par with other American poetry. Piling up on the bed and on every inch of floor is apparently a Kundiman Salon tradition, so there we were. Listening to each person share a bit of art was literally music to my ears. For all of us who love, love, love, language, being in a room where you hear beautiful words, clever words, words that make you laugh and cry, that's heaven on earth. Kundiman inspires me: I want to be better and I think I can get there too. :)

Tuesday, February 21, 2017

Asian-American writers from Coffee House Press

Asian-American writers talk about generations of activism voice

0- BY AANEWS

- IN ASIAN AMERICAN STUDIES · BOOKS · EDUCATION · JOURNALS · POETRY · SPOKEN WORD · STORYTELLING · WRITING

- — 13 FEB, 2017

AAP contributing writer